Your language-teaching mission, should you choose to accept it, is to celebrate women’s history month with your students using engaging resources.

Image source: www.ssf.net/Home/Components/News/News/8573/1809

March is Women’s History Month. Although it is not the only month in which we can celebrate the contributions of women, it’s a great time to remind ourselves to make sure that our curriculum is inclusive of all genders! In the United States, Women’s History Month began as Women’s History Week in March 1978. Educators in Santa Rosa, California wanted to increase awareness of women’s contributions to society and chose a week in March because International Women’s Day falls on March 8. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter made this a week of celebration for the entire country, saying “the achievements, leadership, courage, strength, and love of the women who built America was as vital as that of the men whose names we know so well." In 1987 Congress expanded this celebration to the entire month of March.

Each month I create a booklet for the Edmonds School District to celebrate that month’s equity themes. These “diversity booklets”, which you can check out here, are designed for parents and teachers to use to supplement the existing curricular learning, or to do a fun craft or art project together while celebrating women, Arab-Americans, LGBTQ+ people, etc. Usually, I curate a selection of resources created by other educators, but this month I ended up designing quite a few of my own, and wanted to put them on the blog to share with other language teachers and provide the answer keys for those using the booklets. All of the resources below are in English, but feel free to adapt them to any language for your students!

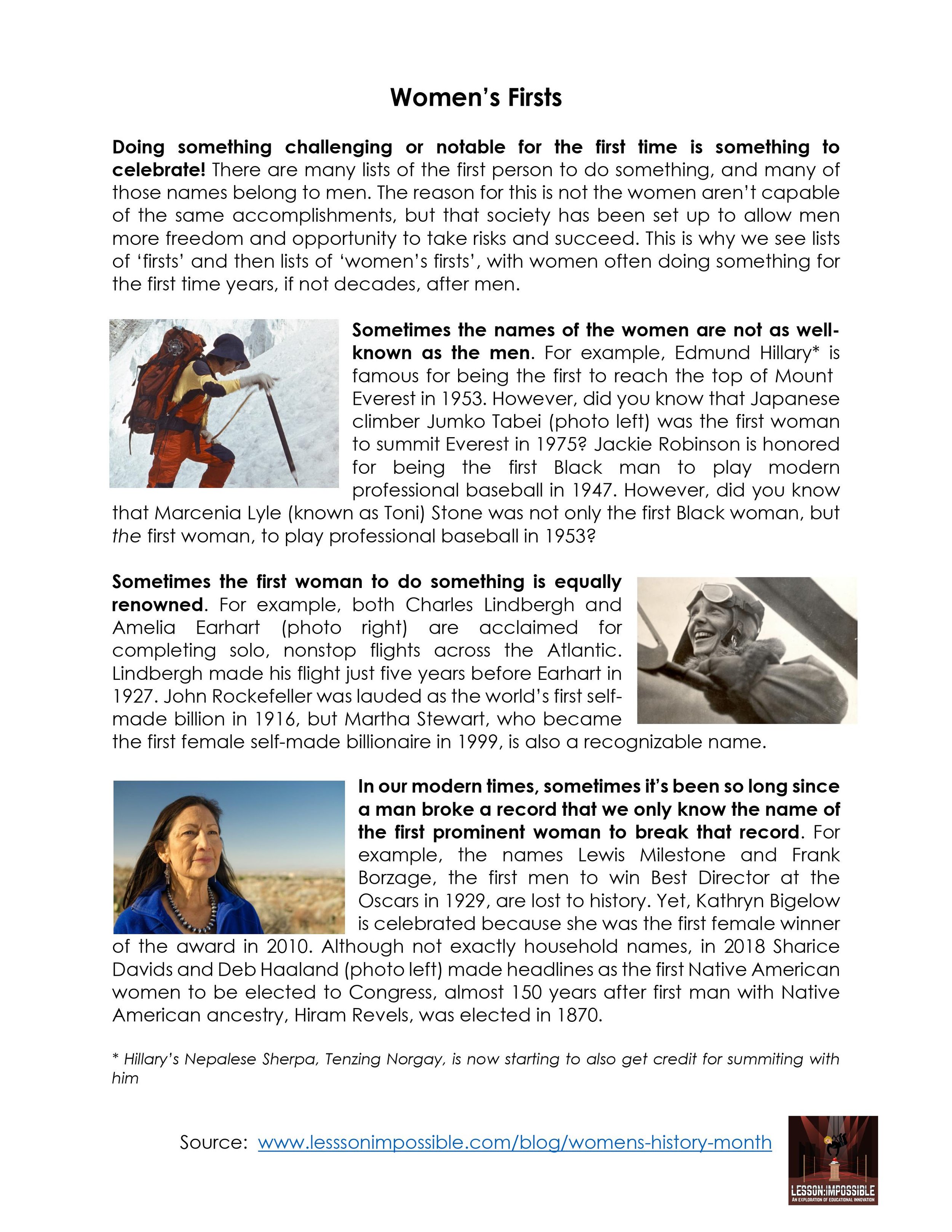

LANGUAGE ARTS/SOCIAL STUDIES: A women’s history firsts reading (written by me) with reading comprehension questions, as well as a follow-up research activity using an instagram framework. For language learners, there is a focus on synonyms, reading dates, and understanding the 5-paragraph essay frame. There is also a chance for students to speak to partners about a discussion question. If you want to extend beyond the text, you can also have students use these firsts as improv prompts.

RESOURCE: Women’s Firsts (4 pages)

RESOURCE: Women’s Firsts Answer Key

COLORING PAGE/SOCIAL STUDIES: A coloring activity that includes the real story of Sacagawea, which is not the white-washed happy narrative that has often been discussed.

RESOURCE: Sacagawea US Coin Coloring Page

MATH: US-based census data for figuring out percentages and reading an infographic.

RESOURCE: Percentages with the Census & Percentages with the Census Answer Key

RESOURCE: Reading an Infographic & Reading an Infographic Answer Key

LANGUAGE ARTS: A reading (“Who is Malala Yousafzai?”) and an activity and reading response. Designed for primary students/ELL students.

RESOURCE: Malala Reading Activity & Malala Reading Activity Answer Key

COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS: Students look at quotes about womanhood, and then find someone in their community who identifies as a woman to provide a quote as well!

RESOURCE: Womanhood Quotes Activity

READ ALOUD: For primary students, a hand-out to send home for students with links to read-alouds of picture books for Women’s History Month.

RESOURCE: Read-Aloud Handout

I’ve made an effort to be as inclusive as possible, highlighting women from a variety of backgrounds. For me, women’s history is also a great time to introduce students to the idea of intersectionality, that is, that our identities contain multiple facets. For example, women such as Mae Jemison, Aprille Ericsson-Jackson, and Katherine Johnson were important because they were both Black and female, as well as many other things, such as daughters, community members, and scientists! I love this quote from Julia Serano, who is a writer, musician and transgender activist: "So long as we refuse to accept that 'woman' is a holistic concept, one that includes all people who experience themselves as women, our concept of womanhood will remain a mere reflection of our own personal experiences and biases rather than something based in the truly diverse world that surrounds us."

How do you celebrate Women’s History Month in your classroom? These resources I’ve shared are American-centric, what are some ways you celebrate women in other countries? Share in the comments!