Your language-teaching mission, should you choose to accept it, is to support your students as they engage in dynamic discussions in the target language.

As teachers of communication, I think we can often forget that we need to teach how to communicate, not just how to use the target language. Participating in a group discussion in an active and respectful manner is a skill as much as correctly conjugating verbs. Those of us who became language teachers probably do a lot of the skills I discuss below innately, but some students, especially the younger ones, can really benefit from explicit teaching.

So, several years ago, after realizing that I needed a strategy to get students to be better group communicators, I talked to the literacy coordinator of my district and together we came up with ‘TALK’ (which we thought was an original idea but is actually similar to a strategy with a different acronym that is found in Shrum & Glisan's Teacher's Handbook and is referenced in the ACTFL Keys to Planning for Learning book by Terrill & Clementi).

I have had a lot of success with this strategy, and it only takes about three to five minutes out of class time but has improved the small group conversations my students have been having in my language classes (see how I adapted into French below) as well as my Social Studies classes!

The beauty is that this can work from elementary school all the way through to senior students and can be used for almost any cooperative task students are engaged in, though I primary used it for small discussion groups.

How it works:

I’ll let students know we’re going to ‘TALK’ today in class, and remind them of the four components:

T – tell an idea

A – ask a question (these can be content based questions or questions that involve someone who hasn’t told an idea yet, such as “what do you think about this Billy?”)

L – listen to others

K – knit ideas together (able to help the group solve a problem or make connections between what everyone has said)

I made big signs for my classroom (printed each page on 11x17 paper) so I could point to it and use it as a reminder.

RESOURCE: TALK classroom signs

I also made table mats that could be printed and laminated as TALK reminders. Another possible use would be to print them and have students put them in their notebooks.

RESOURCE: TALK table mat

At the end of all the class activities and discussions I give them time to reflect. The goal is to be “all talk” but sometimes a student can be an ‘alk’ (asked, listened, helped problem solve, but didn’t contribute new ideas), a ‘lat’ (listened, asked, told, didn’t problem solve), a ‘ta’, ‘kat’ – you get the idea. It gives them concrete goals to work towards and a very quick way of reflecting on how they did that day.

I also would occasionally ask students to reflect more concretely on their TALK skills and use an exit slip to see how they thought they were doing.

RESOURCE: TALK self-evaluation

In doing this activity I actually had one student say “I’m glad I worked with [classmate] because I’m a ‘tk’ and he’s an ‘al’ so together we can help each other be ‘all talk’ – I ask him what he’s thinking so he can add a ‘t’ and then I stop talking while he’s answering so I can be an ‘l’.” While ideally, I’d like them to be sharing and listening for the sake of sharing and listening, if it’s about ‘winning’ the cooperation activity, why not!

How to use this in a non-ELL/English L1 classroom:

I love this strategy so much that I would encourage you to take the time to make an acronym in your target language. It could even be a fun activity to brainstorm ideas with your students and utilize their creativity in creating it. Please also consider sharing what you came up with in the comments!

For my French students I developed P.A.R.L.E (literally “talk” in French).

P – Posez une question (ask a question)

A – Aidez une autre (help another person)

R – Racontez des idées (tell some ideas)

L – Lisez-les ensemble (tie them [ideas] together)

E – Écoutez attentivement (listen carefully)

You’ll notice there’s an extra letter than the English TALK, so I was able to add “Help another person” which is especially important in a language class when some people struggle to find the right word or get their ideas out the way they want to. We also discussed how helping someone else can mean NOT supplying the right word, but letting them engage in productive struggle by using their language strategies (like rephrasing, gesturing, finding a synonym, etc.)

RESOURCE: PARLE signs

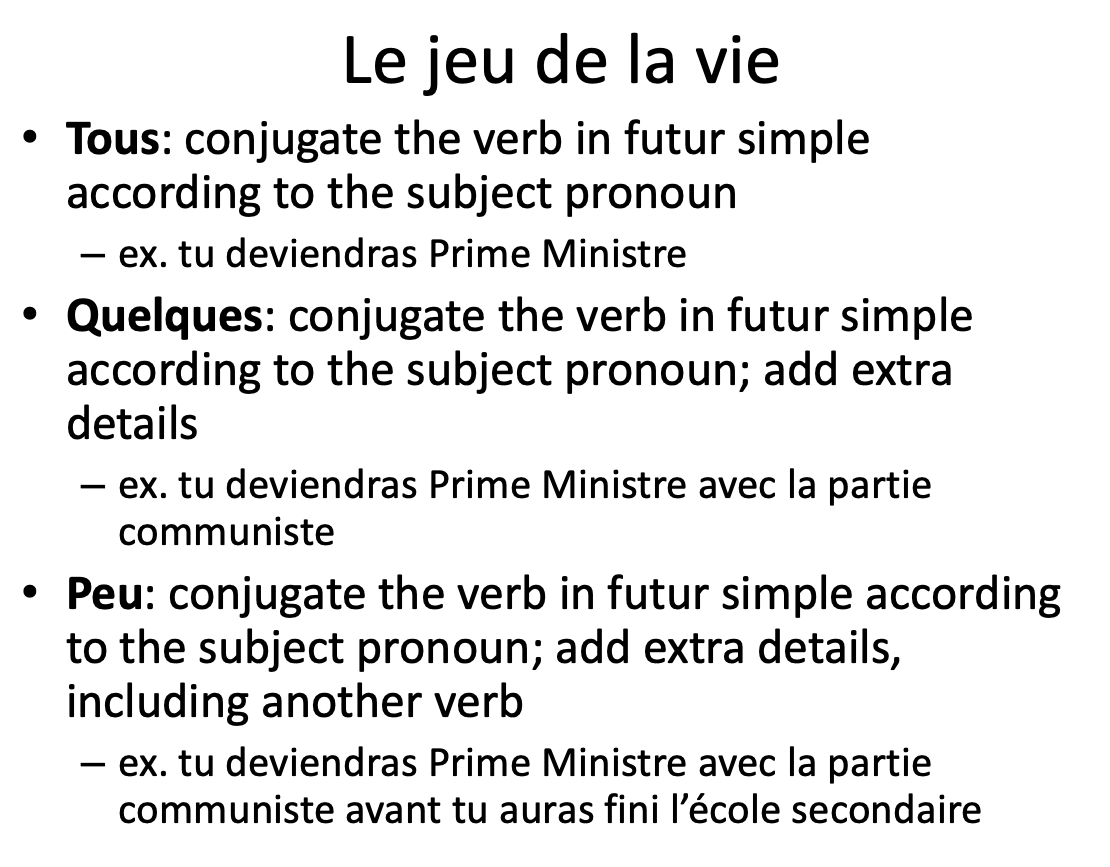

I also developed a guided conversation tool for more advanced French students to use. It guides groups through using a variety of tenses but talking about the same subject (in the example, books) and also gives them a chance to practice PARLE! In my classroom I liked to keep a bucket of activities that were self-explanatory in case I was ever so sick that my note to the substitue could be one line: “please use any activities you want from the green bucket”. In said bucket were some games, improv prompts, and this guided conversation.