Your language-teaching mission, should you choose to accept it, is to incorporate improv games and activities into your language classroom.

Drama is “a wide range of oral activities that have an element of creativity present” (Thorton & Wheeler, 1986, p. 317)

This is part III of a series of posts on using improv in the language classroom.

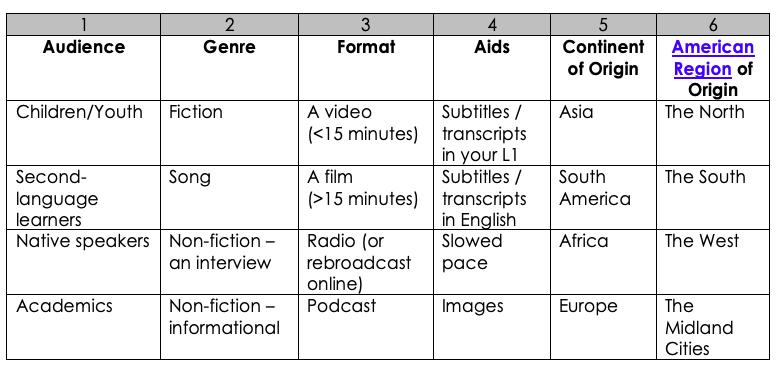

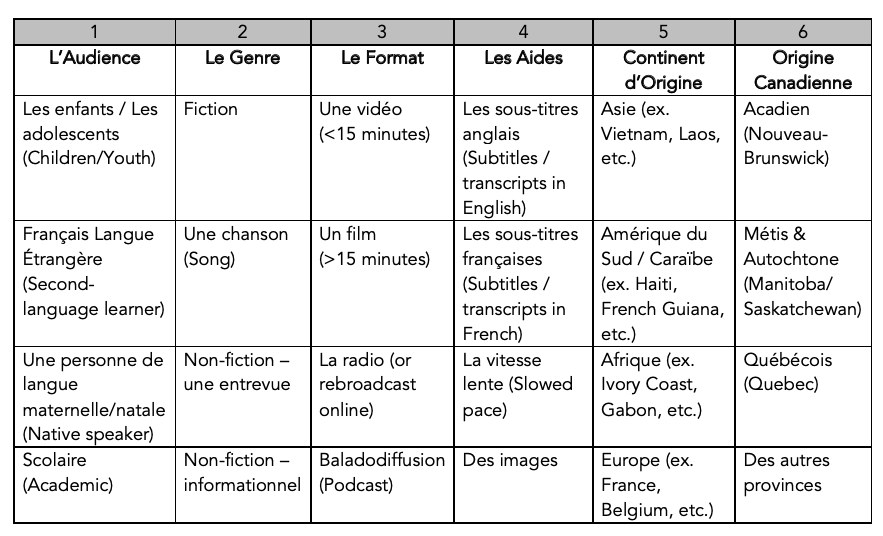

Just because a teacher uses “drama” in their language classroom does not necessarily mean that everyone is on the same page as to what that means, or the philosophies behind their choices. Dr. Kathleen McGovern, (author of the book on improv in the L2 classroom I can’t stop recommending) notes, for example, that a teacher that subscribes to the Audio Lingual Method, who believes that the repetition of scripts is integral to language learning, will have a different approach that a teacher who subscribes to Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), who would forgo scripts for role plays and improvised games to enhance communicative competence. Moreover, a teacher who teaches using the Total Physical Response approach would have students embodying words and phrases, while Total Physical Response Storytelling (while similar in name, not similar in philosophy) would have teachers use comprehensible input and aspects of students’ lives while acting out a story. All of these are technically drama-based teaching, but all are very different! The only thing they have in common is the fact that drama is not the primary focus of L2 instruction, but as a tool to be used to enhance learning.

Therefore, Dr. McGovern, after synthesizing the literature that emerged in the field of drama and L2 instruction over several years in her 2017 article, suggested a system of classifications of common approaches that teachers can use when discussing drama:

Classification 1: Theatrical Performance

Definition: Students study and then perform a play in the target language.

Pros: Introduces students to the target language’s culture.

Cons: The plays chosen will often reinforce the norms of the dominant culture.

Classification 2: Process Drama

Definition: Involves improvised scenes, does not require an audience, and emphasizes learner reflection.

Pros: It has been shown to increase student engagement and participation, reduce anxiety, and result in multi-modal learning.

Cons: The benefits to students’ language learning is correlated to their teachers’ drama experience.

Classification 3: Games and Improvisation

Definition: Teachers use a wide repertoire of theatrical games and improvisation techniques.

Pros: While not specifically tied to a conceptual framework, this approach fits well within CLT’s goals.

Cons: Is a short-term method that relies solely on isolated exercises and is teacher orientated.

Drama is “the literature that walks and talks before our eyes” (Boulton, 1968, p. 3)

McGovern emphasizes that a difficulty in studying drama in L2 education is that drama is not static but constantly evolving. She suggests the following distinctions be made in order to limit confusion:

“Drama” v. “Theater”: Drama should be used to describe students engaging with theatrical activities, while theater should refer to students enacting a performance for an audience.

“Product-based” v. “Process-based”: Product-based drama should be used to refer to an approach in which students study and rehearse a text that they then perform to an audience. In contrast, a process-based approach is one in which students participate in improvisation and theater games and is limited to the classroom.

“Small-scale” v. “Large-scale” forms: Small-scale forms should refer to activities that last only one class or unit and do not result in a final product. Thus, large-scale forms should refer to activities that are script-based and require more time.

Accordingly, in the spirit of Dr. McGovern’s desire to have clear definitions when talking about using drama in the L2 classroom, I want to clarify that when I talk about improv on this blog, I am talking about something that can be described as:

Games and Improvisations. While Process Drama uses improv games, it is part of a much deeper philosophy of continuous, embodied learning that emphasizes learner identity. Games and Improvisation is the use of one-off activities that are incorporated into a teacher’s existing curriculum, and is not considered the curriculum itself. For more information on Process Drama I recommend Erika Piazzoli’s 2018 book “Embodying Language in Action: The Artistry of Process Drama in Second Language Education”.

Drama. While sometimes my students perform for an audience of their classmates, that is not the goal of the activities we do.

Process-based. There is no product. As Margaret Piccoli notes, one of the best parts of improv is that it forces us to be in the moment because it disappears as soon as it is complete!

Small-scale. Any language teacher that takes on the task of staging a complete theatrical performance that takes months to rehearse, build, and promote gets all my admiration. However, that is the opposite of what I’m talking about!

While I was able to teach with no problems before coming across these classifications, I think there is a lot of value in being able to specify what we do. For one, it allows us to reflect on the choices we make. For example, if I subscribe to CLT, and I have my students memorizing scripts, then there is clearly a conflict between my philosophical framework and the activities I use, and I need to make some changes. Furthermore, specificity gives us better understanding. If another teacher and I are both using “drama” in our French classes, we might have very different assumptions about what is happening in each others’ classrooms. Additionally, for research purposes, once everyone gets on the same page with definitions, it’ll make finding articles that are actually relevant that much easier!

Also, I think there is tremendous value in all areas being discussed! Galante (2011) notes that “while drama offers opportunities for learners to use prior knowledge of the L2 in a creative manner, theatre focuses on accuracy and aspects integral to the performance such as vocal projection and comprehensible speech” (p. 276). While my interests have leaned towards the process-orientated drama side of things, if I had a class that wanted to do a theatrical production, or needed to focus on accuracy, vocal projection, and comprehensible speech, I would love to do a big end-of-year presentation.

Source: McGovern, K. R. (2017). Conceptualizing drama in the second language classroom. Scenario (Cork), XI(1), 4-16.

Do you think definitions are helpful when discussing drama? How would you categorize your own use of drama in your language classroom? Share in the comments!